Adventures of a Honu Guardian

Although my interest in sea turtles was always listed on my resume, I have to admit it leaned more toward a professional hobby. I never applied for a sea turtle grant. I never published a sea turtle paper (although I do have a completed manuscript that I never submitted for publication on human impacts to green turtle behavior in Hawaii). And I did attend 2 meetings of the International Sea Turtle Symposium on Biology and Conservation, once in San Diego, and once in Brisbane, Australia.

|

| Posing by one of my posters in Brisbane! |

Most surprising (to me), I did once try to get myself stranded for a summer on French Frigate Shoals, a speck of sand in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, to tag and measured green sea turtles (that’s another story).

I remember the spark that ignited my interest in sea turtles. I was diving with naturalist Bob Kern in Hanauma Bay, Hawaii (a marine reserve), when we spotted a young honu (the Hawaiian name for a green turtle) swimming toward us. We paused, neutrally buoyant in the water column, and it came closer and closer, until it tried to bite my hair! Then it swam over to Bob and tried to bite his nose! I think this was an immature, naive turtle just exploring its environment, and we were not threatening. Luckily, Bob had his camera.

|

| Tagging netted green sea turtles, Florida, as part of the sea turtle biology course. |

I also took a week-long sea turtle course on Maui taught by Dave Gulko, who wrote a book on sea turtles. My registration for this course was paid for by the group Friends of Hanauma Bay. I owe them!

This led to Caroline and me spending 4 days on Lady Elliot Island in the Great Barrier Reef (Australia, ‘natch) in 2009. It took about 45 minutes to walk completely around the island, and we did it twice a day. You can easily see the fresh drag marks in the sand from female green turtles coming ashore to lay their eggs, and then leaving. We stayed up one night till about 3 am to watch an entire nesting cycle. In the morning, we’d look for tracks and nests, and search for disoriented hatchlings that wandered in the wrong direction. These hatchlings were collected in buckets and released that night. We met biologist sea turtle biologist Emma Doyle on this trip, and she shared some of her photos.

|

| Here Caroline is holding a flashlight that she will use to direct the hatchlings back into the ocean. She stood in the surf, pointing the flashing down between her legs, and the hatchlings just “ran” through her legs! |

I’ll return to this story in a minute. Back in Utah, I lectured on sea turtles for a full week every year in my “Living With Wildlife” course. I also gave presentations on sea turtles for Audubon, high school, elementary, and middle school audiences, as well as at Hanauma Bay.

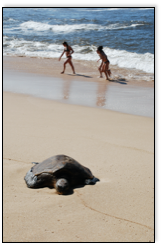

On Oahu, I was introduced to the “Honu Guardian” program developed by THE honu expert, George Balazs, and worked to protect the honu at Laniakea Beach on the North Shore. This was an uncontrolled portion of beach, so surfers, dog walkers, swimmers, tourists, photographers, locals, and sun worshipers were all present. Some people really didn’t know how to behave around sea turtles. The volunteer protection program is now called:

Mālama i nā honu

|

| Caroline looking for foraging honu at Laniakea Beach. |

|

|

| Honu Guardians would mark off the areas where honu would come ashore to bask, keeping visitors at a safe distance. Note the red rope outlining a safe viewing distance. |

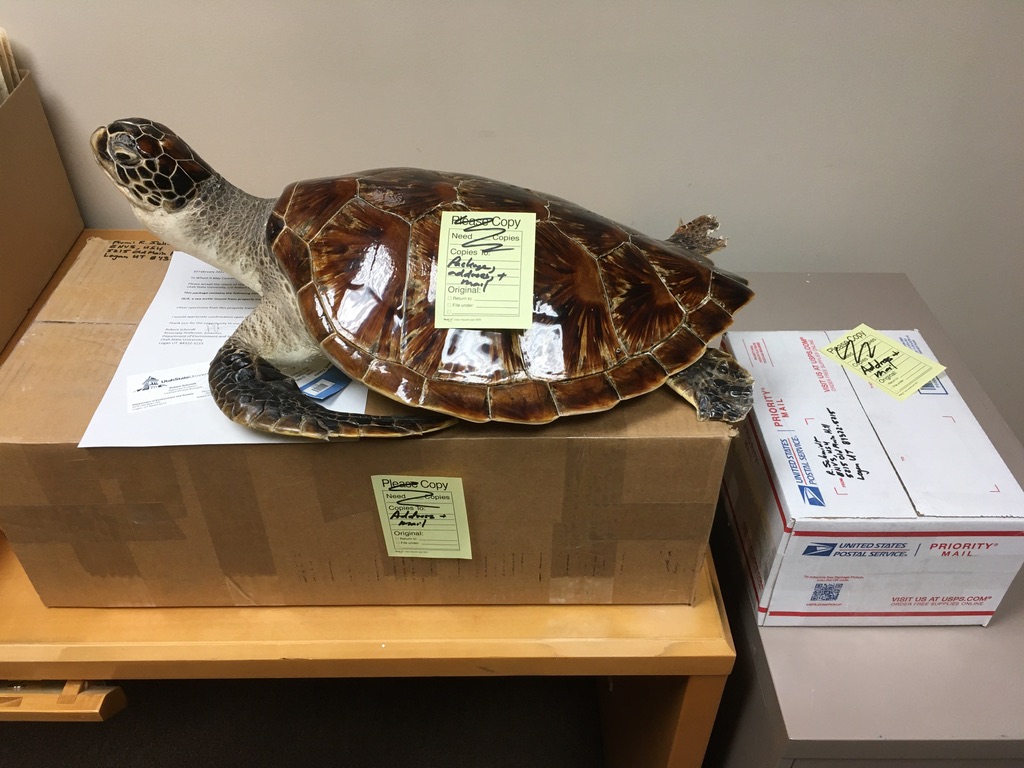

For years I had a mounted green turtle in my office as a display. The animal was on loan to me from the US National Wildlife Property Repository (where confiscated protected wildlife are kept), and when I retired, I sent it back to them. I had also borrowed a piece of green turtle leather, one shoe (size 10.5) made from green turtle leather, and a decorative hair comb made from the carapace (shell) of a hawksbill turtle. These pieces of real sea turtles had a powerful effect on students when I lectured about threats to sea turtle populations.

•••••

Okay, it’s time for my sea turtle tale. This happened one morning on Lady Elliot Island, probably the morning following our late night nesting watch, and Caroline was still asleep. I was walking around the island myself, looking for new drag marks. How I enjoyed this walk! No human sounds, no human tracks, no trash. It felt very primeval.

This day, there was a low tide and no wind. The inner reef was dead calm. I came across a nesting drag mark, and followed it up the rise of the beach to where the vegetation started. On a very active nesting beach, there are only so many great places to dig a nest, so it is not unusual for a new nest to dig up an older nest, leaving the older eggs exposed for scavengers and the elements. Now, I don’t have any photos. Our iPhone battery (and this was the FIRST iPhone, model 1) had been depleted, and external battery packs hadn’t been invented yet. Our cabin had a solar light, and there was no charging option. So I’m going to recreate the scene with other photos.

Right at the edge of the vegetation, I was peering around, looking for eggs and the new nest.

|

| Holding sea turtle eggshells from a previous season. |

Out of the corner of my eye, I perceive movement near my feet. I’m startled… I didn’t want to step on any creature. But what I see is the rear of a hatchling, sticking out of ghost crab hole. When you are walking on a beach in early morning, you may notice little mounds of sand, next to holes of varying sizes. These are the burrows of ghost crabs, and ghost crabs consume organic debris on a beach, and are predators of hatchling sea turtles as well.

|

| Photo courtesy of Susan Scott. |

.jpg) |

| Photo courtesy of Susan Scott. |

I gently pulled the hatchling out of the ghost crab hole. Both eyes were missing. I thought I read once that ghost crabs blind or maim hatchlings before pulling them into their burrows, thereby preventing the hatchlings from escaping (a “system” for live food storage). But I can’t find a reference to these behaviors, so it may be unfounded.

I’m standing there, alone, wondering what I should do next. Do I put the hatchling back in the hole, returning the crab’s prize? Do I euthanize the hatchling, which was struggling weakly?

Let me describe the natural history of a hatching event. The eggs hatch over 2-3 days, and the hatchlings move toward the surface. A NOAA website describes the process as follows:

“When the tiny turtles are ready to hatch out, they do so virtually in unison, creating a scene in the sandy nest that is reminiscent of a pot of boiling water. In some areas, these events go by the colloquial term “turtle boils.” Once hatched, the turtles find their way to the ocean via the downward slope of the beach and the reflections of the moon and stars on the water. Hatching and moving to the sea all at the same time help the little critters overwhelm waiting predators, which include sea birds, foxes, raccoons, and wild dogs. Those that make it through the gauntlet swim to offshore sargassum floats where they will spend their early years mostly hiding and growing.”

Once they hit the water, a hatchling goes into what is called “frenzy swimming.” They start swimming, nonstop, for hours, and this behavior appears to be innate. The rationale is that these tasty morsels need to get into deep water and ocean currents, away from the many nearshore predators that are looking for them.

This initial trip to the ocean is all-consuming. It is their life. It defines a sea turtle. I felt that giving the little guy a taste of the sea was the least I could do.

I carried the hatchling to the shallow water, and gently lowered it into the water. There was an immediate bloom of red blood surrounding the head. It sank into 5-6 inches of water. The water was crystal clear, with zero wave action. I wondered if there might be another hatchling in that hole. I followed my tracks back to the original ghost crab burrow, dug a bit of the sand away to look inside, and saw nothing. So I returned to the water to see the dying hatchling. I was away for maybe 20 seconds.

There was nothing there.

The water was still clear and calm. What happened?

Three things could have happened. One, a bird could have dove in and grabbed the hatchling. But there would have been ripples in the water, and there were none. Plus, I didn’t see a bird, before or after.

Two, a fish could have eaten the hatchling. Again, however, there were no ripples in the water, and the water was so shallow, I really have to think that a fish big enough to grab the hatchling would have made ripples.

So I believe scenario three occurred. I put that hatchling in the water, where it revived and started its frenzy swimming. Obviously, it wasn’t going to live, but the general consensus of sea turtle conservationists is that only 1 out of 1-2000 hatchlings born actually survive to reproductive age. Mortality is high.

So I believe the hatchling revived, the innate behavior of frenzy swimming kicked in, and that doomed hatchling actually became a bonafide sea turtle, coming out of the egg, digging to the surface, feeling the warm sand on its flippers, then recognizing oceanic water for what it was, its home. It swam for however long it could, then returned to the sea the nutrients its mother had foraged from the sea to make her.

The circle of life.

|

| When sea turtles are digging, then filling in their nest, their powerful front flippers throw sand around. The sand sticks to the wet carapace (shell). When they return to the sea, I leave them with a very temporary, finger drawn symbol of my affection for them. |

Comments

Post a Comment